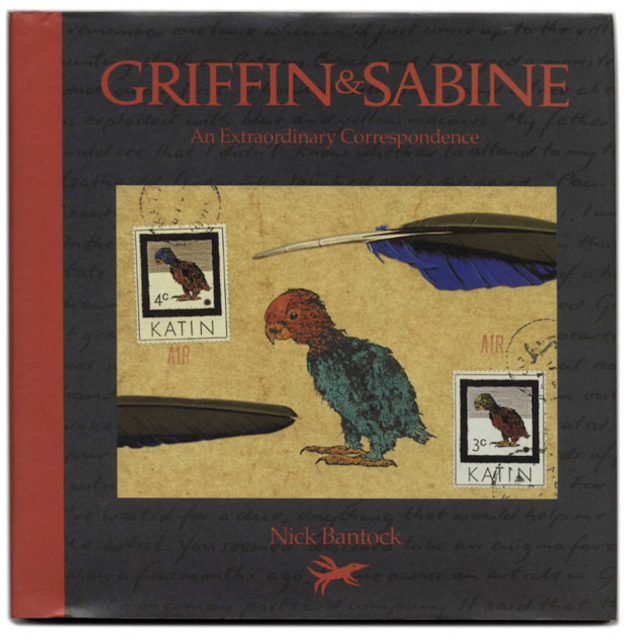

"Griffin & Sabine: An Extraordinary Correspondence" by Nick Bantock (1991)

"I crave an art that passionately transcends the mundane instead of being a device for self-deception." - Griffin Moss "Griffin & Sabine" is an epistolary book, holding the postcards and letters between Griffin Moss and Sabine Strohem. Sabine initiates the correspondence with a familiarity that doesn't seem shocking until it is revealed that Griffin has no idea who she is. From there, the story becomes brilliantly clairvoyant, adding touches of romance beyond the physical, yet, very *metaphysical* indeed. The book itself is interactive. The artwork is note-worthy, being both surrealist and avant-garde, making "Griffin & Sabine" deserving of multiple readings. Some pages have envelopes, and the reader is welcomed into opening those envelopes and pulling out the letters, both typed and handwritten, within. This tactile experience is fundamental to reading the book, adding an exciting element of voyeurism to its textuality. Perhaps "Gri...