"Neuromancer" by William Gibson (published 1984)

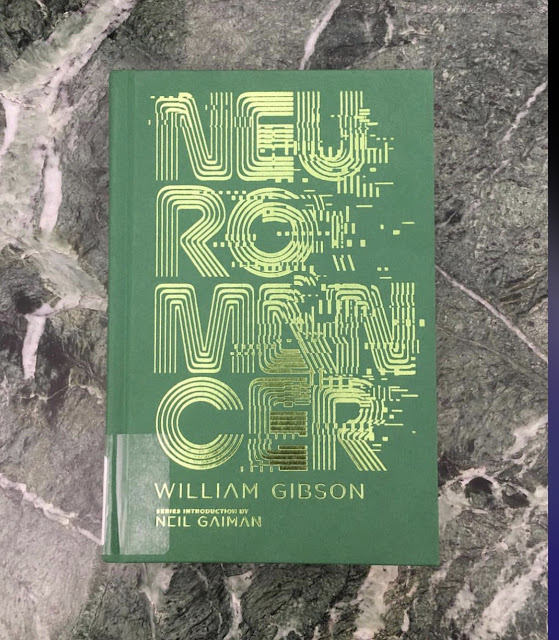

Some are familiar with Gibson's science fiction novel, "Neuromancer", now a classic (see the new, gorgeous 2016 edition from Penguin, complete with an inspiring introduction from Neil Gaiman), because it predicted the internet before the internet was invented. "Neuromancer", published in 1984, is a text that also depicts humanity's addiction to technology, a relationship that becomes indistinguishable from what is known as reality. These are two great reasons why the novel should be highly noted, but not the reason why the book should become, in my eyes, a Great Book, a Classic, a Literary Masterpiece, that should, perhaps, be required reading centuries from now, taught by professors and doctors hired by universities.

My Goodreads review gives "Neuromancer" four stars, and not the highest, five, because it is, I believe, not entirely accessible. The book is not easy to read, and I don't think it should be, even to the expense of less comprehensibility. The narrative is written in hypertext form, a postmodern writing style (that has since become an actual technological phenomenon) that focuses on continuous action, with stories within stories and plots bleeding into one another, without a lot of room to understand the machinations of the writing while one is actually reading. Exacerbating this are Gibson's descriptions of abstract concepts that are difficult to contend with generally. For example, Gibson's famous coining of the term cyberspace is as such:

"Cyberspace. A consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions of legitimate operators, in every nation, by children being taught mathematical concepts... a graphic representation of data abstracted from the banks of every computer in the human system. Unthinkable complexity. Lines of light ranged in the non space of the mind, clusters and constellations of data. Like city lights, receding..."

Tonight I finished reading the book for the fourth or fifth time. I can't remember exactly how many times I've read it now. The book is no less hard to read each time I pick it up, yet, it is always rich as ever. Years ago, ten years to be exact, I completed a thesis paper that used a lot of "Neuromancer" for source text. I came up with a theory called techno-subjectivity: a condition of the postmodern, globalized world in which a subject no longer needs, or no longer can relate to, a national identity, and also faces three different crises; one of identity itself, one of community, and one of history. "Neuromancer" provides an excellent literary example of techno-subjectivity. I simply could not find examples that fit so perfectly into my theory than "Neuromancer. Literature or critical theories anywhere else simply did not have it:

"And flowed, flowered for him, fluid neon origami trick, the unfolding of his distanceless home, his country, transparent 3-D chessboard extending to infinity. Inner eye opening to the stepped scarlet pyramid of the Eastern Seaboard Fission Authority burning beyond the green cubes of the Mitsubishi Bank of America, and high and very far away he saw the spiral arms of military systems, forever beyond his reach."

The rich abstraction of "Neuromancer" is a gold mine for certain, specific types of persons, and deemed to be just so for me. I don't want to get into the schematics of my thesis paper on techno-subjectivity here in this "review". Still, another important facet of my paper was that the techno-subject is someone symptomatic of Cold War and post Cold War politics. An anxiety, a nervousness, a feeling of unbridled competition with no exact source, a suicidal drive to get to the heart of the matter, which simply could not and cannot be found in identity politics, nor linear histories, nor subcultures of any kind. Ultimately, a fragmentation of the self, a self reduced to pattern recognition (funnily, the title of one of Gibson's later novels) and the flesh (or "meat" as it's referred to in "Neuromancer". Read a description of one of the characters named Riviera:

"She also said he was legally stateless... he was a product of the rubble rings that fringe that radioactive core of Old Bonn..."

If any of this subject matter interests you at all - read "Neuromancer". Nevermind its symbols of Christianity - which are never obvious or crude anyway - but more because of its politics of the present moment. Science Fiction can take us to this point: to what is really going on, not to some old nostalgia or yearning for an older or future time that we were never a part of. Or, never meant to be a part of. "Neuromancer" will probably give you a little headache, as it should. As it should.

I read an essay titled "Stealing Kinship: Neuromancer and Artificial Intelligence" by Carl Gutierrez-Jones which absolutely blew my mind. Simply put, Gutierrez-Jones took the novel as an example of fictional literature taking aim at Cartestian duality (the mind/body split). Furthermore, that the story aimed at breaking down that split, to show how it simply doesn't and cannot exist. The one needs the other, there is not other way for reality to exist. What Neuromancer does is show how understanding this can be problematic. There is the meat, the flesh, that wants what it wants, and there is another drive of the personality, the ego and everything else that does what it does:

"'I had a cigarette', Case said, looking down at his white knuckled fist. 'I had a cigarette and a girl and a place to sleep. Do you hear me, you son of a bitch? You hear me?'"

When the main character Case's animal instincts and drives are shattered - for there are other things in this world which we have to deal with at a complex level, no? - he's angry and depressed and frustrated. All this other technological stuff is part of the fabric of his world and he must contend with them in order to continue living, though he does not really want to, he is nonetheless motivated by his need for insight (see the Gutierrez-Jones paper for more). There are moments like this, too, human moments:

"He couldn't think. He liked that very much, to be conscious and unable to think. He seemed to become each thing saw: a park bench, a cloud of white moths around an antique streetlight, a robot gardener striped diagonally with black and yellow."

I'm not going to ruin the story and give you the plot (and yes, I've read it enough times that I can go through plot points chronologically). Just know that "Neuromancer" challenges the ideas we associate with love, relationships, our bodies, our selves, and does so by inserting that obscure, sometimes aggressively ignored entity, mysterious and powerful and ubiquitous, that we call technology, letting it spread through the veins of the story like a circuitboard lit up by a continuous electrical impulse.

My Goodreads review gives "Neuromancer" four stars, and not the highest, five, because it is, I believe, not entirely accessible. The book is not easy to read, and I don't think it should be, even to the expense of less comprehensibility. The narrative is written in hypertext form, a postmodern writing style (that has since become an actual technological phenomenon) that focuses on continuous action, with stories within stories and plots bleeding into one another, without a lot of room to understand the machinations of the writing while one is actually reading. Exacerbating this are Gibson's descriptions of abstract concepts that are difficult to contend with generally. For example, Gibson's famous coining of the term cyberspace is as such:

"Cyberspace. A consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions of legitimate operators, in every nation, by children being taught mathematical concepts... a graphic representation of data abstracted from the banks of every computer in the human system. Unthinkable complexity. Lines of light ranged in the non space of the mind, clusters and constellations of data. Like city lights, receding..."

Tonight I finished reading the book for the fourth or fifth time. I can't remember exactly how many times I've read it now. The book is no less hard to read each time I pick it up, yet, it is always rich as ever. Years ago, ten years to be exact, I completed a thesis paper that used a lot of "Neuromancer" for source text. I came up with a theory called techno-subjectivity: a condition of the postmodern, globalized world in which a subject no longer needs, or no longer can relate to, a national identity, and also faces three different crises; one of identity itself, one of community, and one of history. "Neuromancer" provides an excellent literary example of techno-subjectivity. I simply could not find examples that fit so perfectly into my theory than "Neuromancer. Literature or critical theories anywhere else simply did not have it:

"And flowed, flowered for him, fluid neon origami trick, the unfolding of his distanceless home, his country, transparent 3-D chessboard extending to infinity. Inner eye opening to the stepped scarlet pyramid of the Eastern Seaboard Fission Authority burning beyond the green cubes of the Mitsubishi Bank of America, and high and very far away he saw the spiral arms of military systems, forever beyond his reach."

The rich abstraction of "Neuromancer" is a gold mine for certain, specific types of persons, and deemed to be just so for me. I don't want to get into the schematics of my thesis paper on techno-subjectivity here in this "review". Still, another important facet of my paper was that the techno-subject is someone symptomatic of Cold War and post Cold War politics. An anxiety, a nervousness, a feeling of unbridled competition with no exact source, a suicidal drive to get to the heart of the matter, which simply could not and cannot be found in identity politics, nor linear histories, nor subcultures of any kind. Ultimately, a fragmentation of the self, a self reduced to pattern recognition (funnily, the title of one of Gibson's later novels) and the flesh (or "meat" as it's referred to in "Neuromancer". Read a description of one of the characters named Riviera:

"She also said he was legally stateless... he was a product of the rubble rings that fringe that radioactive core of Old Bonn..."

If any of this subject matter interests you at all - read "Neuromancer". Nevermind its symbols of Christianity - which are never obvious or crude anyway - but more because of its politics of the present moment. Science Fiction can take us to this point: to what is really going on, not to some old nostalgia or yearning for an older or future time that we were never a part of. Or, never meant to be a part of. "Neuromancer" will probably give you a little headache, as it should. As it should.

I read an essay titled "Stealing Kinship: Neuromancer and Artificial Intelligence" by Carl Gutierrez-Jones which absolutely blew my mind. Simply put, Gutierrez-Jones took the novel as an example of fictional literature taking aim at Cartestian duality (the mind/body split). Furthermore, that the story aimed at breaking down that split, to show how it simply doesn't and cannot exist. The one needs the other, there is not other way for reality to exist. What Neuromancer does is show how understanding this can be problematic. There is the meat, the flesh, that wants what it wants, and there is another drive of the personality, the ego and everything else that does what it does:

"'I had a cigarette', Case said, looking down at his white knuckled fist. 'I had a cigarette and a girl and a place to sleep. Do you hear me, you son of a bitch? You hear me?'"

When the main character Case's animal instincts and drives are shattered - for there are other things in this world which we have to deal with at a complex level, no? - he's angry and depressed and frustrated. All this other technological stuff is part of the fabric of his world and he must contend with them in order to continue living, though he does not really want to, he is nonetheless motivated by his need for insight (see the Gutierrez-Jones paper for more). There are moments like this, too, human moments:

"He couldn't think. He liked that very much, to be conscious and unable to think. He seemed to become each thing saw: a park bench, a cloud of white moths around an antique streetlight, a robot gardener striped diagonally with black and yellow."

I'm not going to ruin the story and give you the plot (and yes, I've read it enough times that I can go through plot points chronologically). Just know that "Neuromancer" challenges the ideas we associate with love, relationships, our bodies, our selves, and does so by inserting that obscure, sometimes aggressively ignored entity, mysterious and powerful and ubiquitous, that we call technology, letting it spread through the veins of the story like a circuitboard lit up by a continuous electrical impulse.

Comments

Post a Comment