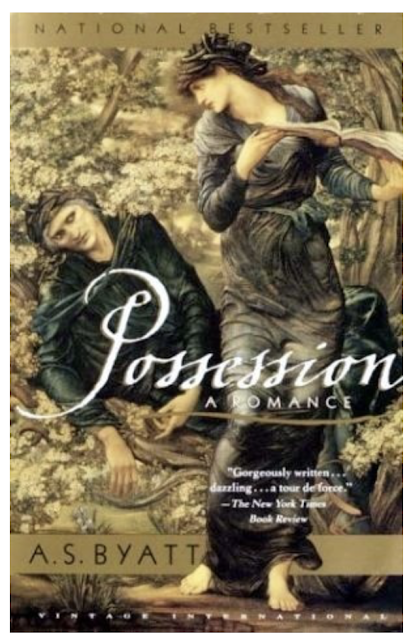

"Possession" by A.S. Byatt (published 1990)

A work of art can be understood as something to one, and something completely different to another. And then, it means something to the author. Sometimes there is a line of clarity, where everyone agrees, and other times the ideas produced by a work are so vastly different that we wonder how to make sense of it at all. We all know and have felt this frenzied state of interpretation. Moreover, we go back to old and new pieces time and time again; a song, a book, a poem, a painting, and as we experience it there is another realization: that time itself has changed the thing, placing it into newer, broader categories of meaning and truth.

A.S. Byatt's Possession, winner of the Man Booker Prize in 1990, is a perfect representation of that kaleidoscopic manifestation of art, lived by its creator and then posthumously, and then into academic elucidation. The story, which claims many voices, is mastered by the study of what begins as a singular poet: Randolph Henry Ash. The study of Randolph Henry Ash's poetical works and biographical life is undertaken by Roland Michell, a poor yet passionate scholar, who accidentally finds drafts of a love letter inside of an old, crumbling, and very dusty book he leafs through at the university library. Something about these beginnings of love letters - which are in fact primary sources - sparks a bright fire in Michell, who feels the urgency in Ash's words, despite Michell finding them almost a century after they are written. He takes them into his possession (not quite legally) and becomes determined to find out what woman the letters were addressed to.

The doctoral student who picks a particular subject of study, especially one who clearly isn't in it for the money, is here given such heartbreaking dimension in Byatt's fictional form. Roland is a devotee of Randolph Henry Ash, and upon finding these never before seen letters, the gravity of what such a finding might mean weighs down on him like a heavy cloak, where he can see what's right in front of him, but not at all the entire picture. Because the poet Randolph Henry Ash is a key figure in the academic community, having had museums, lectures, presentations, special collections, critical texts, biographies, etc. emerge in his name, Roland knows that his discovery might change the face of poetry as it stands in his world of 20th century England. Yet, he dares not tell his professor Dr. Blackadder, just yet. Something within urges him beyond a desire for recognition. Byatt makes it clear that Roland is personally attached to Ash's work. And why wouldn't he be? He's the one dedicating his life to this undertaking, refusing meaningless jobs and not quite lavishing his grounded girlfriend, Val, with attention (though she is the bread-winner).

Now, as stated previously, Possession is a novel of many voices. As the reader turns each page, s/he will become familiar with Ash's work as well. The pages are graced with poetry, and one might become curious to grapple with Ash's symbolism too. It is sensual, it is romantic, it is classic, it is pagan, it is Christian, all at once, and it is spellbinding:

These things are there. The garden and the tree

The serpent at its root, the fruit of gold

The woman in the shadow of the boughs

The running water and the grassy space.

They are and were there. At the old world's rim,

In the Herperidean grove, the fruit

Glowed golden on eternal boughs, and there

The dragon Ladon crisped his jeweled crest

Scraped a gold claw and sharped a silver tooth

And dozed and waited through eternity

Until the tricksy hero, Herakles,

Came to his dispossession and the theft.

- Randolph Henry Ash from "The Garden of Proserpina", 1861

More voices follow in Byatt's writing, clear as crystal. After consulting a university friend of his, Roland becomes acquainted with Maud Bailey, a scholar of the poetess Christabel LaMotte. As they adventure into the world of these two poets, they find, and not without a lot of wit and even more cunning, intense love letters. They spend days in the library studying them. And who does Byatt take with them, but the reader, laying down long, exquisite, and heart-wrenching notes written by such individual characters, each in his/her own style and philosophy, that the book becomes alive with multiple worlds inhabiting and crossing time and space without one hint of crude time travel, but by the pure and simple artifact of the written word.

As pieces of the story and placed together, as the scholars work, as secrets are revealed, not just one, but many, Byatt does not fail to include the innate self-reflexivity of the academic world, the snobbery of their critics (at one point a solicitor mentioned just how narcissistic scholars must be), the naivety and greed and kindness of the lower-class English countrymen, and the general aura of late 20th century England, and later from the eye of an American professor. Byatt is impressive because she does not fail to provide us with wonderfully imperfect, wonderfully human characters, brought together by something the majority of the population doesn't give one wit about: uncovering the full story no matter to what losses. The lingo of academia is here, with it's comments on phallocentricity, feminism, post-modernism, structuralism, deconstruction, semiotics... but these words become more than the language of the pretentious, hopefully, because they are the vocabulary of truth, for some, setting them free.

In Possession, two romances run together at once and in different forms of passion. Love is shown in many opposing ways, yet is always recognizable as love. Boundaries are broken always with the bravery and courage of the human soul and nothing else. The book traverses expanses of land and space with great detail, and readers will get a picture of the English land and its culture. But far from all this, A.S. Byatt's Possession wells up the heart and eyes with its surprises, twists and turns, and knowledge that the truth is slow and steady and never complete but always there, waiting, only graspable in certain moments when the light and dark reach the object at just the right angle, illuminating, if only for a second, that precipice of eternity.

"Roland read, or reread, The Golden Apples, as though the words were living creatures or stones of fire. He saw the tree, the fruit, the fountain, the woman, the grass, the serpent, single and multifarious in form. He heard Ash's voice, certainly his voice, his own unmistakeable voice, and he heard the language moving around, weaving its own patterns, beyond the reach of any single human, writer or reader... Ash had started him on this quest and he had found the clue he had started with, and all was cast off, the letter, the letters, Vico, the apples, his list."

Comments

Post a Comment